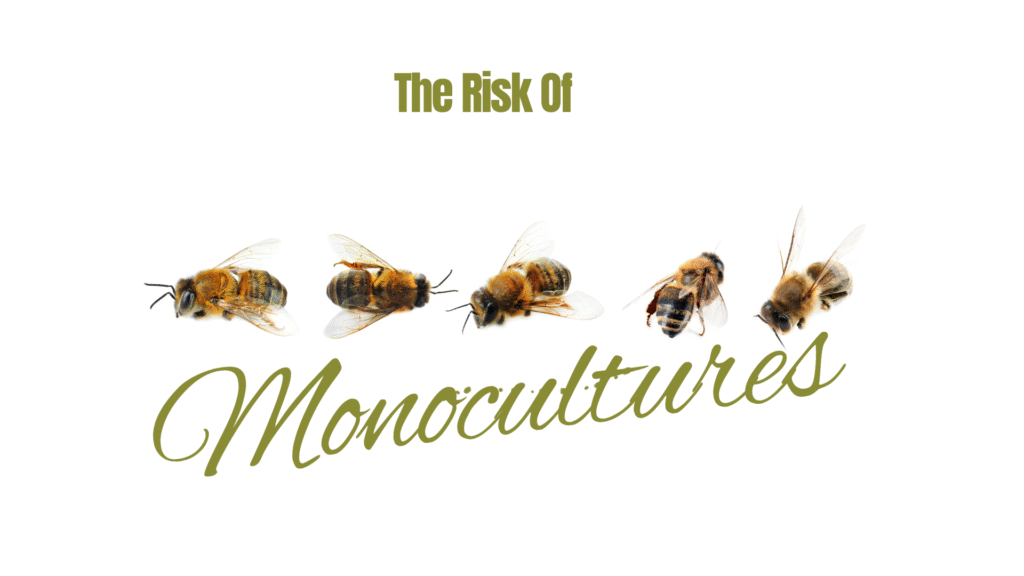

In California’s Central Valley, you’ll find miles upon miles of almond trees—so many that the state now produces more than 80% of the world’s almonds. On the surface, it looks like a triumph of modern farming. Every acre is optimized, every tree planted in straight, orderly rows. Yields are higher than ever.

But there’s a hidden cost. Almond trees can’t pollinate themselves. They depend on honeybees. And because these orchards are vast monocultures, they offer bees just one type of food, for a few weeks each year. To meet demand, farmers truck in millions of bees every spring, hauling them across states. The bees work intensely for that short window, often under stress from pesticides and the exhausting travel. The result is that bees are dying.

Monocultures appear efficient in the short term, but they strip away the diversity and slack that make an ecosystem adaptable. What looks like progress is actually fragility in disguise.

Roger Martin

Besides one natural disaster could put 80% of the world’s almond production at risk. The challenge of a monoculture is that every little crease of inefficiency is ironed away until it is stiff as an overstarched shirt.

Hyper-efficiency is like planting only almonds. You may get more output today, but you weaken the resilience and creativity needed to survive tomorrow.

The Folly of Net Promoter Scores

I had taken my car for a routine service to the dealer. While handing over the keys at the end of the day the service station manager told me, “We have a small survey we ask all customers to fill up.” She handed over the form and said, “You have an overall rating to choose from 1 to 10. Ten is the highest score and one s the least. Can you please rate us at 10 because less than 10 means I won’t get my bonus.”

It is not uncommon to see that the sales team gets high NPS scores but the business is stagnant. Yet NPS seems to be the Holy Grail of so many businesses.

In business, monocultures don’t always look like orchards. Sometimes they look like organizations where everyone is trained to think the same way, chase the same metric, or optimize for the same short-term result.

Think of a company that runs on one number—say quarterly earnings, or Net Promoter Score. Just like the almond farmer who plants nothing but almonds, leaders narrow their focus to what feels efficient: squeeze costs, maximize output, push everyone toward the same target.

At first, it works. Earnings look strong. Metrics go up. The rows are neat, the system hums.

But then, the hidden costs appear. Employees stop experimenting because there’s no room for “inefficient” trial and error. Managers ignore long-term investments in skills because they don’t move the needle this quarter. The company becomes dependent on one “pollinator”—a single star performer, one big client, one hot product line.

And like the bees in the almond orchards, those pollinators burn out. Innovation dries up. The organization becomes brittle.

Roger Martin’s book set me thinking about short term thinking that plagues so many organizations. They invest in technical training but shrug away soft skills training. Diversity of thought, slack for experimentation, and investment in soft skills may look inefficient in the short term—but they’re the biodiversity that keeps organizations alive when the climate shifts.

Want to listen to more ideas before you decide to read the book? Here is Roger Martin at Google talking in detail about the book