Family, success and selfhood definitions vary

Imagine trying to assess a world-class violinist using a basketball metric. They may score zero on dunks—but does that mean they lack talent? Success means different things to someone who is growing up in rural India as compared to a kid growing up in Silicon Valley.

The Eastern philosophy stresses group harmony, roles and duties. The Western self values personal goals, choice and independence. A married man asking their parents for advice will trigger smirks among colleagues in the West. They will view the parents having failed in their duty to make their progeny independent. In

That’s precisely what happens in talent management systems that fail to recognize a core anthropological truth: The self is a cultural construct. Who we are, how we behave, and what we reveal (or conceal) about ourselves at work is shaped by deep cultural coding—expectations, rewards, punishments, and shared scripts.

Yet most performance reviews, leadership assessments, and potential ratings still assume a narrow model of “the ideal employee”—typically assertive, expressive, confident, visible, and individualistic. This model fits some cultures perfectly. But for millions of employees worldwide, it can feel like trying to perform a symphony with the wrong instrument.

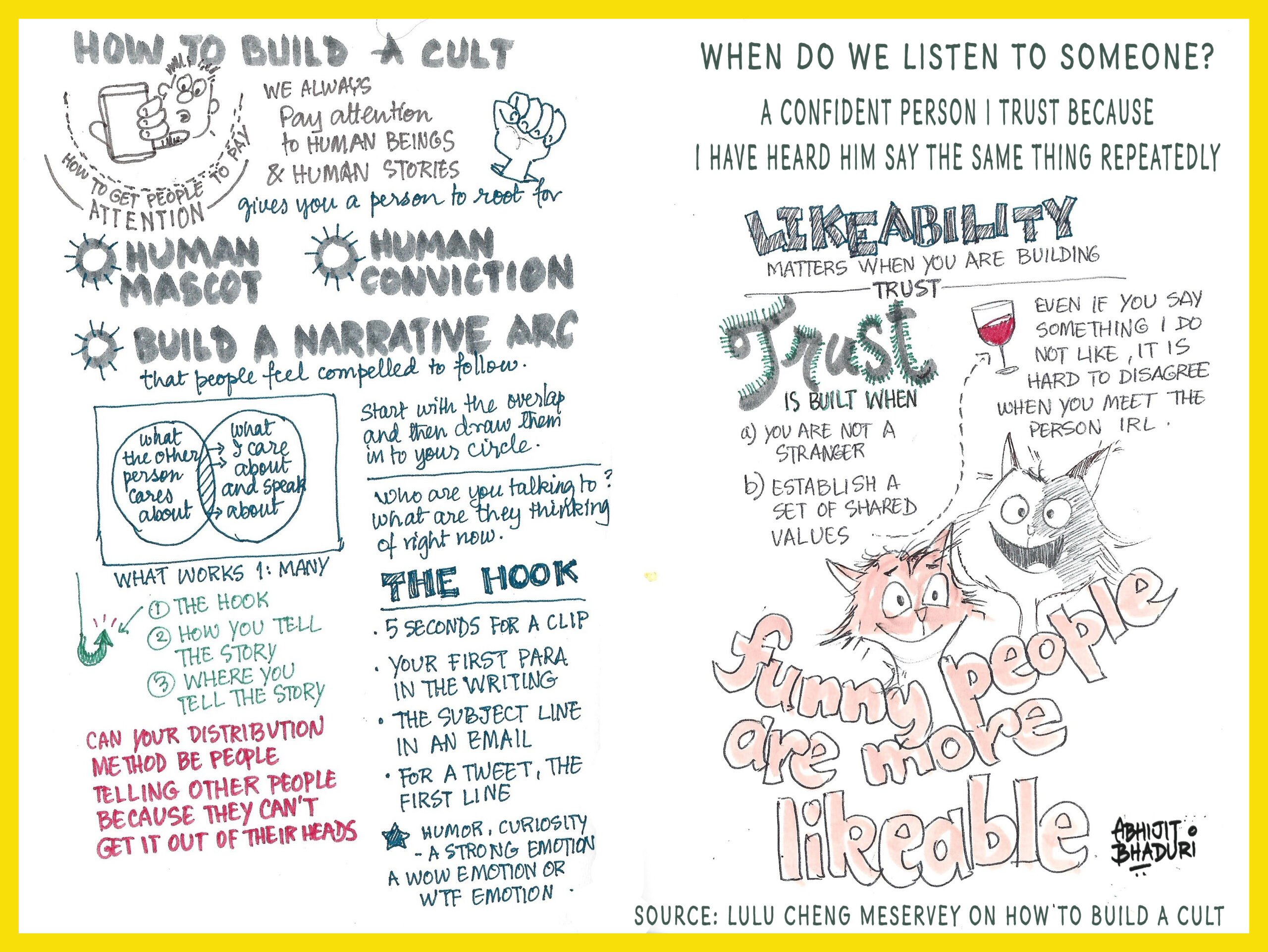

So what if we flipped the script? What if HR became anthropology-aware?

What if…

HR teams got trained in Anthropology

To know ourselves we must know others. To manage talent, we must manage meaning.

Here’s how five everyday workplace behaviors reveal the cultural construction of the self—and how organizations can use this lens to unlock hidden talent. It may be worth looking at many Talent Management practices with the lens of anthropology.

1. Silence Isn’t Apathy—It Might Be Wisdom

In parts of Nigeria, especially among the Yoruba, silence isn’t passivity—it’s poise. A measured pause or quiet presence may be a cultural expression of maturity and leadership.

HR Insight: Don’t assume talk time equals talent. In meetings, encourage managers to note not just who speaks, but who listens with intent and offers reflective insight. Use storytelling or written reflections to surface ideas from those who process quietly.

2. Watch the “We” Language in India

Many Indian employees, particularly in group-oriented work cultures, instinctively say “we built this” even for solo achievements. It’s not a lack of ownership—it’s a sign of humility and team-first values.

HR Insight: Standard self-evaluation forms asking, “What did you achieve?” may miss these contributions. Instead, ask peers: “Who made your success possible this quarter?” Social proof reveals what modesty may hide.

3. Is Avoiding Eye Contact a Sign of Respect?

In East Asia and parts of the Middle East, direct eye contact with authority can be seen as disrespectful—not confidence.

HR Insight: Rethink your “executive presence” rubric. A high-potential leader may show power through clarity, humility, or collective thinking, not charisma. Consider context-sensitive coaching that embraces quiet gravitas as much as polished presentation.

4. Speaking Up Isn’t Always Psychological Safety

In China, harmony is prized. Voicing dissent openly—even in a “safe space”—can be viewed as threatening the group’s cohesion.

HR Insight: If feedback culture requires public candor to “prove” openness, you may be misreading silence. Use confidential pulse surveys or third-party feedback loops. Train managers to read indirect cues like withdrawal, hesitancy, or silence not as disengagement—but as data.

Read this: Low engagement is a social issue

5. The Hidden Power of Humility in Thailand

In Thai workplace culture, boasting—even in mild forms like LinkedIn posts—can feel inappropriate. Humility is dignity.

HR Insight: If you rely on self-nomination for leadership programs or awards, you’ll miss these stars. Instead, use peer nominations or manager flags to identify talent. Normalize saying “Tell us who deserves to be seen.”

Culture Isn’t Just a Diversity Box—It’s a Design Principle

Anthropologist Charles Lindholm writes, “We can really know ourselves only if we know others, and we can really know others only if we know the cultures in which they (and we) exist.”

Talent management isn’t just a numbers game. It’s a meaning-making game. To attract, grow, and retain top talent across cultures, we must first recognize that talent doesn’t always speak in a language we’ve been trained to hear.

It may bow instead of boast. It may collaborate instead of compete. It may whisper instead of shout.

But it’s still talent.