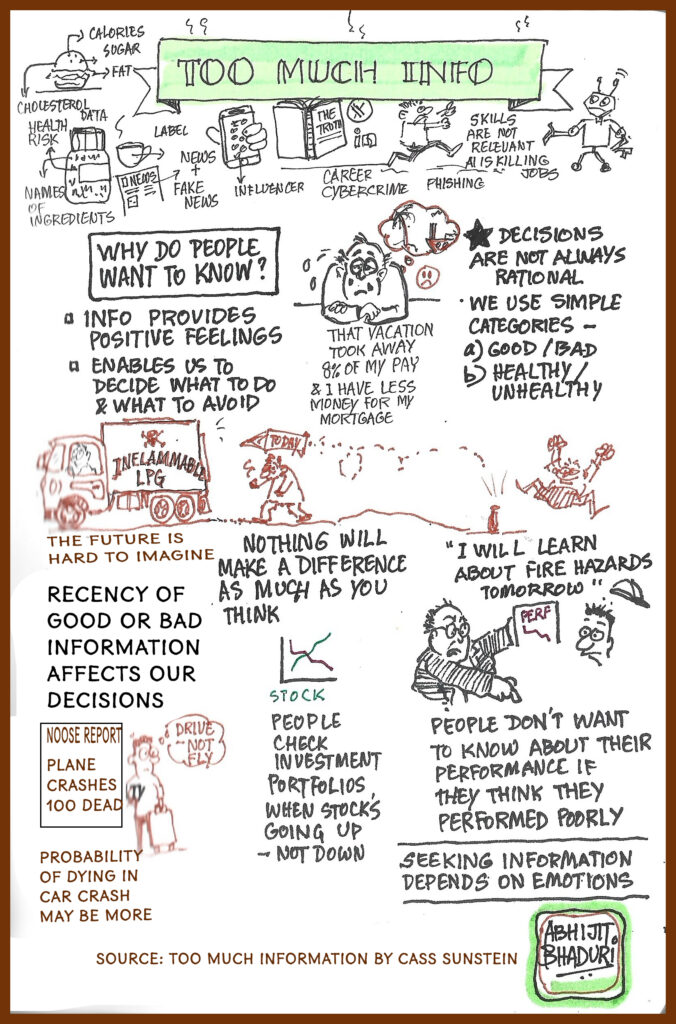

We are bombarded with information. From labels on food to ads to a million dashboards at work, health checkups … we seek information based on how it makes us feel. It’s not how much we know. It’s what we do with it

Why More Information Doesn’t Always Mean Better Decisions

Every Monday morning, a manager opens their inbox to a flood of dashboards. One from HR showing attrition risk. One from Finance on budget utilization. One from Learning & Development summarizing course completions. At the same time, Slack pings with updates on employee engagement scores, the new travel policy, and the company’s quarterly carbon footprint report.

There’s data everywhere—insight, nowhere.

In organizations today, we often confuse the abundance of information with the clarity of knowledge. We believe if we just share more—metrics, disclosures, benchmarks, scores—people will be empowered to act.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: not all information is helpful. Some of it confuses us. Some of it overwhelms us. And some of it quietly makes things worse.

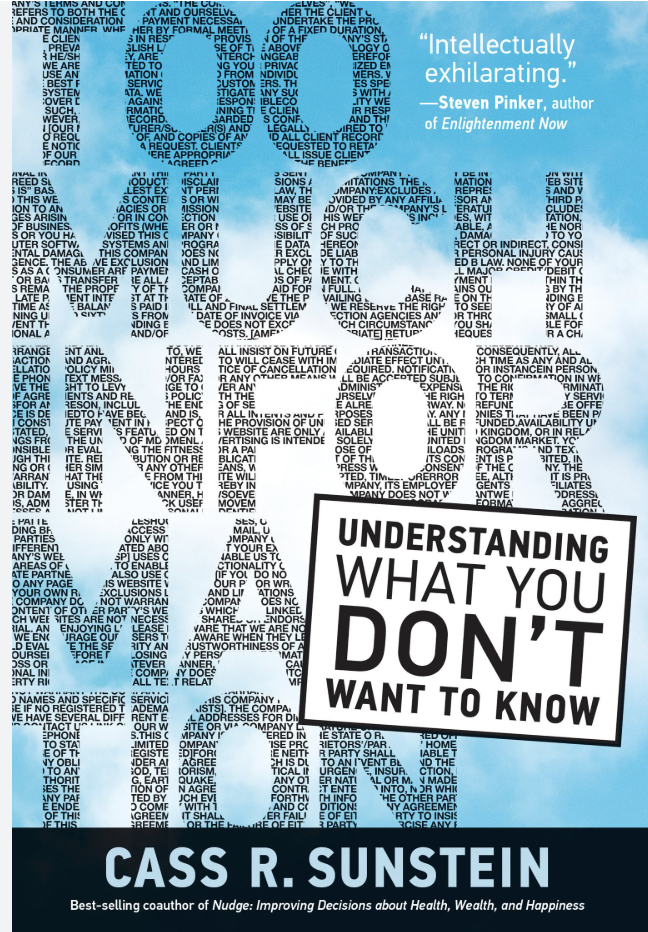

Cass Sunstein’s book Too Much Information puts a spotlight on this dilemma. He argues that information should not be shared for its own sake. It should be shared only when it improves lives or helps people make better decisions.

That’s a simple idea—but one we forget in our well-meaning pursuit of transparency.

Data without empathy is noise

Sunstein tells the story of how calorie disclosures at movie theaters, though scientifically valid, can “ruin popcorn” for many. People are there to enjoy themselves, not to think about saturated fat in the dark. In fact, some people would pay not to see that information. That doesn’t mean the disclosure is wrong—but it does mean we should think about how and when it’s delivered.

We’ve all felt this. A medical report filled with scary numbers we don’t understand. A performance dashboard that flags us “at risk” without context. A long policy update we scroll through, feeling guilty for not reading.

The problem isn’t the data. It’s that data without empathy is noise

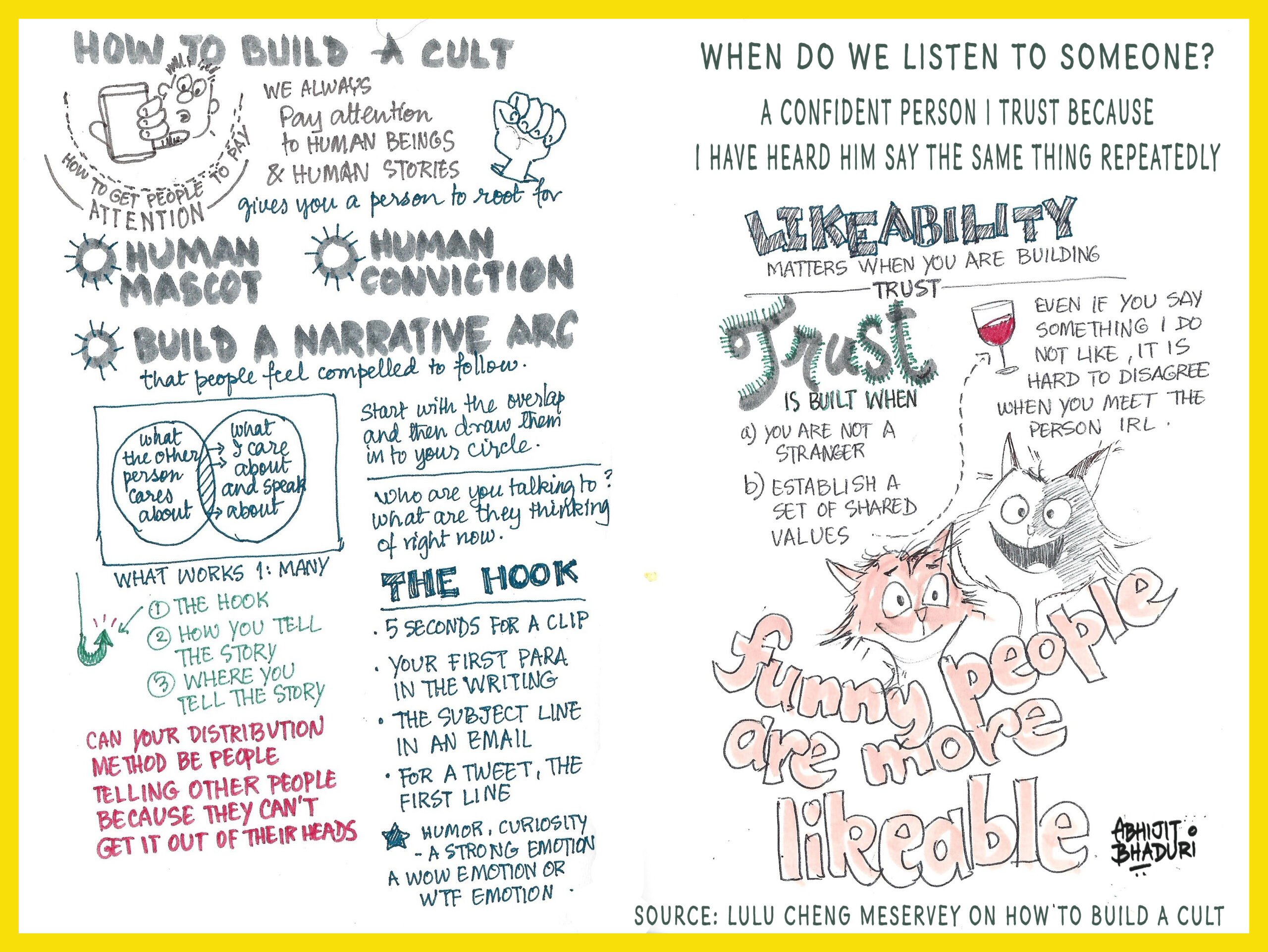

“We use emotions to process information”

Humans don’t just process information rationally. We also absorb it emotionally. Sometimes what looks like empowerment is actually quiet distress. Sometimes what’s meant to “nudge” us ends up making us anxious, confused, or disengaged.

That’s why a human-centered approach to information is so important.

Before we push a new disclosure, a new form, a new message—we need to ask:

Will this help someone make a better decision?

Will this improve their well-being in any way?

Could it unintentionally cause stress, shame, or inaction?

If the answer is no, it might be time to hold back.

Applying this to talent management

In the world of HR, we’ve leaned hard into dashboards, pulse surveys, and people analytics. But information without intention can backfire.

Consider this:

- An employee sees their low engagement score in a team report and feels exposed, not heard.

- A succession list is circulated but never discussed—leaving some feeling invisible and others anxious.

- A manager is told one of their team members is a “high flight risk” based on an algorithm—but isn’t given the tools to have an honest conversation.

Leaders must be taught the emotions that the dashboards will generate

Just like a museum curator doesn’t show every artifact, HR leaders must curate what truly matters, delivered in ways that support action, dignity, and growth. Share data with context. Pair metrics with stories. Turn insights into conversations, not just reports.

When information is designed for humans—not just systems—it becomes a compass, not a foghorn.

Let’s move from overload to clarity. From disclosure to understanding. From data dumps to meaningful dialogue.

Because in the end, it’s not how much we know. It’s what we do with it that makes the difference.