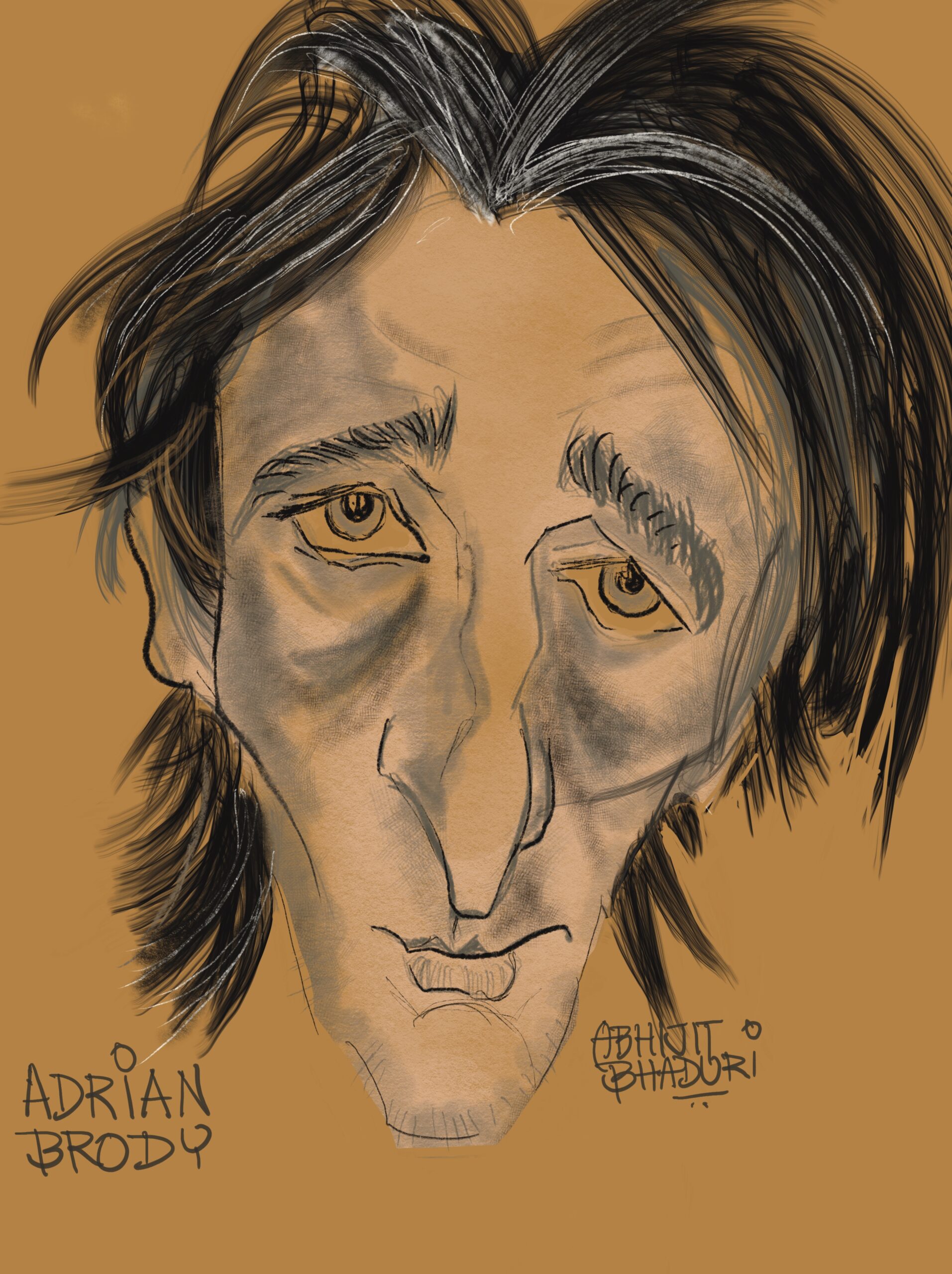

Adrian Brody: Art Imitates Career in The Brutalist

Adrian Brody has a knack for playing characters who suffer beautifully. In The Pianist, he endured war and starvation with haunting resilience. In The Grand Budapest Hotel, he was a delightfully sinister antagonist with a sharp mustache. And now, in The Brutalist, he takes on the role of an architect whose career is held hostage by an overbearing employer who believes he owns him. If Brody’s career were a screenplay, it would have similar highs, lows, and a few existential crises in between.

In The Brutalist, Brody plays László Toth, a Hungarian architect who flees Europe, seeking freedom and a fresh start. Instead, he finds himself bound to a patron who mistakes financial investment for soul ownership. This employer isn’t just demanding—he’s the human equivalent of a restrictive non-compete clause, suffocating every ounce of artistic independence. László’s dilemma is painfully relatable: work that pays the bills but slowly erodes his identity.

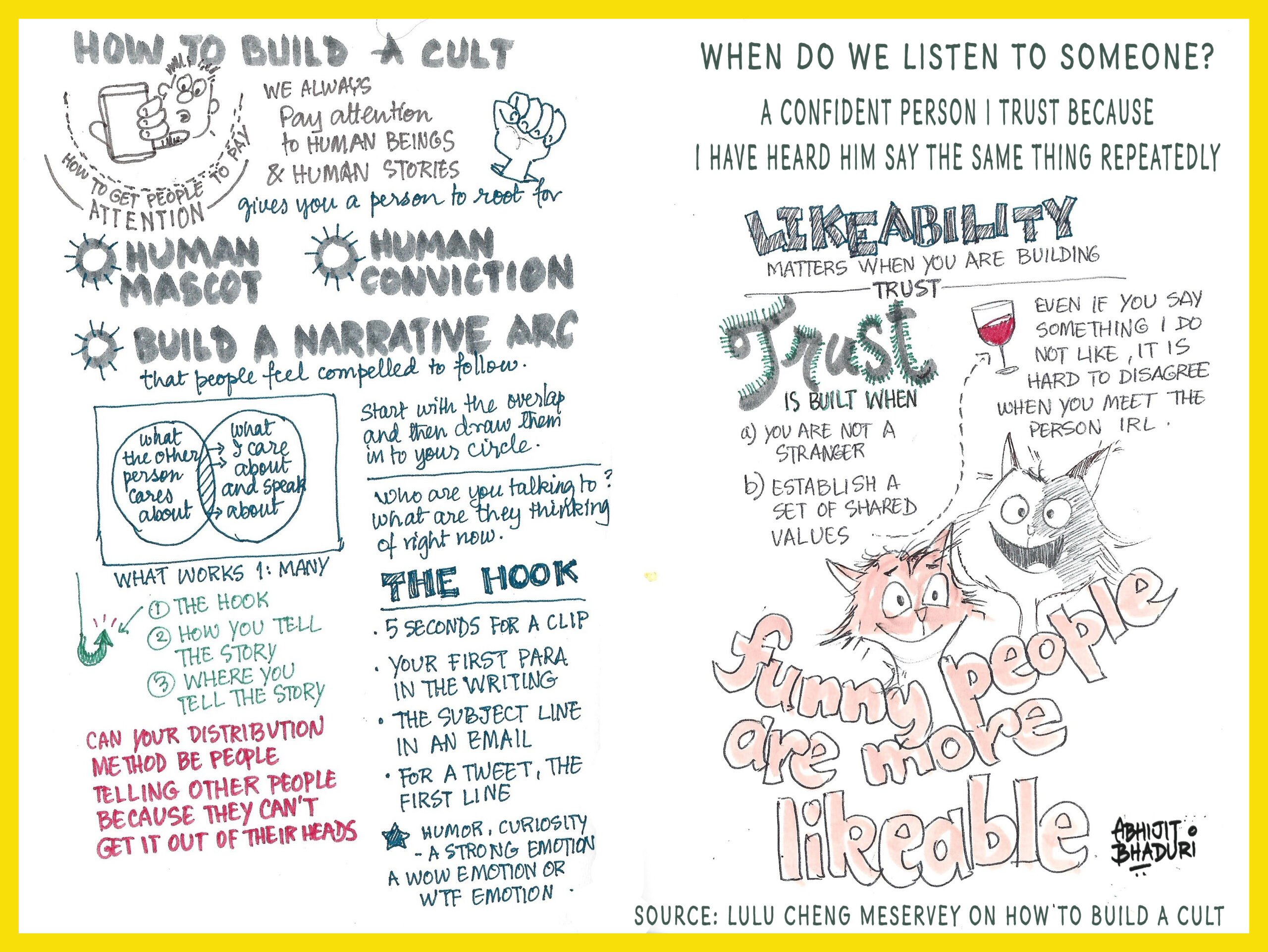

Now, let’s talk about Brody himself. After his Oscar win for The Pianist—the youngest Best Actor winner at the time—Hollywood was ready to anoint him. But success is a fickle patron. Rather than taking the conventional blockbuster route, Brody made unpredictable choices. He worked with indie directors, took eccentric roles (see: Wes Anderson), and occasionally dabbled in projects that made audiences go, “Wait, that’s Adrian Brody?” His journey had all the hallmarks of László’s struggles—early promise, external pressures, and the eternal question: Do I follow the money or my passion?

Like László, Brody has had to navigate a system where creative control is a rare luxury. Hollywood, much like László’s tormenting employer, rewards conformity over originality. Actors, like architects, are often at the mercy of studios (or patrons) who believe that a paycheck is synonymous with ownership. Brody, much like his on-screen counterpart, has had to fight for agency in his career. While László battles artistic oppression, Brody has managed to carve out a career that balances prestige and personal passion—a rare feat in an industry that prefers predictability over reinvention.

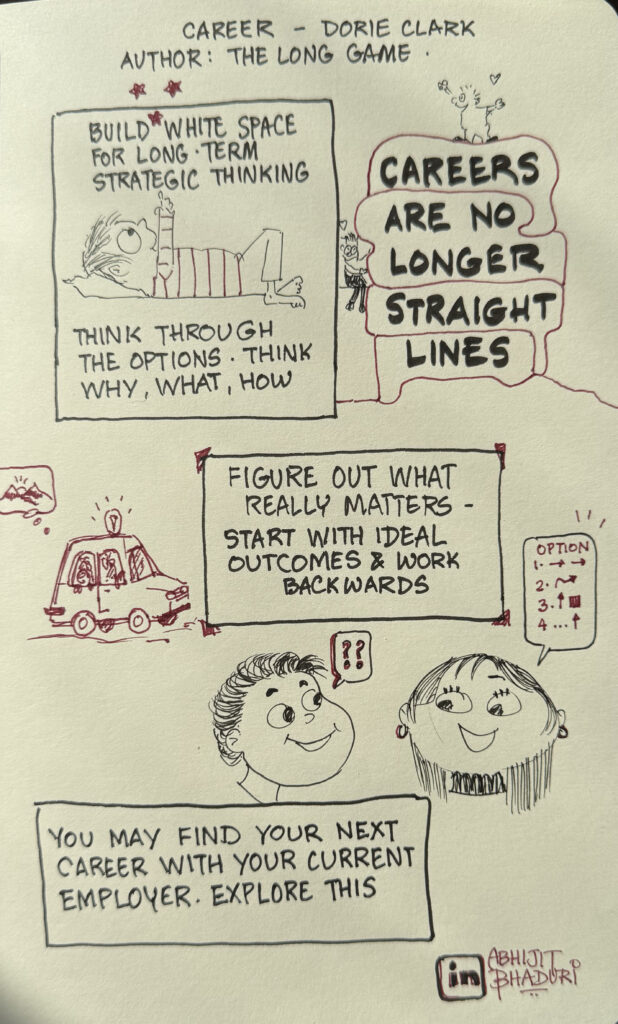

Which brings us to Dorie Clark’s The Long Game. Clark argues that career success isn’t about overnight wins but about strategic patience, selective choices, and playing the long game. Both Brody and László illustrate this beautifully. László, despite his employer’s grip, never truly surrenders his artistic identity. Brody, despite the industry’s expectations, continues to take roles that intrigue him rather than ones that fit a conventional mold. Clark’s philosophy—creating space to think, rejecting short-term distractions, and working toward long-term success—echoes in Brody’s career choices. His ability to endure, reinvent, and stay relevant without selling his soul makes him the perfect real-life embodiment of The Long Game.

So, whether you’re an architect trapped under a tyrannical patron, an actor navigating Hollywood’s highs and lows, or just someone trying to make your mark—Brody and Clark have the same advice: patience, strategy, and never letting anyone believe they own you.